As of January 1st of this year, Chinese firms that list abroad are no longer required to seek approval from the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) – the government agency in charge of regulating foreign exchange market activities, and managing the state foreign exchange reserves – in order to repatriate foreign exchange raised. Now, firms will simply need to register the IPO or other foreign fund-raising activity, with any proceeds freely transferable back. Related rule changes have also made it much easier for firms listed overseas to repatriate excess foreign exchange originally remitted from China with SAFE approval for such purpose as acquisitions or share buybacks. The new guidelines published on December 31st mark another significant step by the Chinese authorities in gradually loosening capital controls introduced to the value of the renminbi in support of the country’s export industries.

Also coming into effect on the same day was the removal of daily caps on banks’ forex positions, to be replaced with a system of weekly checks. By this move SAFE hopes to offer banks more flexibility in managing their forex positions. Additionally, banks no longer need to tally their positions to their foreign currency loan-to-deposit ratios, and are no longer necessarily required to always be long on the US dollar. These two rules were introduced in 2013 to stem the renminbi’s appreciation, and have been lifted in light of the currency’s weakening by 2.5% in 2014, the most significant movement since the currency’s revaluation in 2005. In light of the broad-based firming of the US dollar expected in 2015 as the euro slides, further regulatory efforts to loosen transfer restrictions can be expected.

Go west

Outside of Hong Kong, the US is the most popular place for Chinese companies to list abroad. Indeed, China is the third largest source of companies listing in the US, behind the US itself and Canada. Over 80 Chinese companies have listed across the NYSE’s main and smaller boards, with a total market cap approaching US$1.5trn; over a dozen companies listed in 2014 alone. The most recent – and highest profile – foreign listing was the e-commerce company, Alibaba Group Holding, which in September 2014 raised US$25.1bn on the NYSE. Setting a record for the largest IPO ever, Alibaba become the latest Chinese listing on the exchange. Valued at some US$250bn, it is the second largest internet company in the world after Google. Some of the money raised will remain offshore to fund foreign acquisitions, but the company also intends to invest heavily in expanding its services domestically, necessitating the repatriation of funds.

Singapore hopeful of new Chinese listings in 2015

Singapore is another popular overseas listing location, with some 130 of the 770 companies listed on the Singapore exchange coming from China. The last IPO there was in 2013, but according to the exchange’s head of listings, Lawrence Wong, a number of Chinese manufacturers, property developers and miners are looking to float there in 2015 in light of recent regulatory changes making it easier for firms to list.

Canada, once host to a peak of 53 Chinese listings in 2010 with a market cap of C$12.8bn (US$10.9bn), has fallen out of favour as a listing destination. The number of companies has fallen to 37 at present, with a combined worth of only C$3.8bn.

Reservations about domestic listing

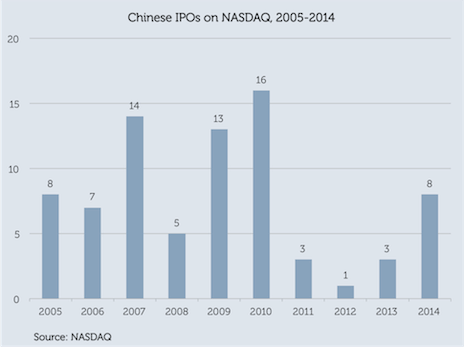

Access to investor capital interested in getting exposure to the Chinese growth story is one particular draw of foreign listings, especially in the US where there has been most activity. There are other factors, however, which have encouraged Chinese firms to look overseas to raise capital. The fanfare and success of the Alibaba float conceals some local concerns that independent entrepreneurs, such as Alibaba’s Jack Ma, are better served and rewarded abroad. Indeed, while rumours that Mr Ma was planning to emigrate from China proved false, a survey conducted by Barclays in September found that nearly half of the country’s high net worth individuals (with US$1.5m of assets) are looking to leave in pursuit of better educational and employment opportunities for their children, and better economic security. The Wall Street Journal (paywall) reported that local academics and securities analysts criticised China's corporate and securities rules for being outdated and not suited for entrepreneurial firms, and the competence of the management of the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges. Indeed, Alibaba was but the latest of a string of Chinese tech companies that have listed abroad; JD.com was also recent, but major internet and tech firms such as Sina Corporation and Baidu chose to list on NASDAQ in 2000 and 2007 respectively, and Tencent Holdings picked Hong Kong for its 2004 IPO.

Professional services firm PricewaterhouseCoopers expects around 200 Chinese companies to launch IPOs on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets in 2015, representing an increase of 60% from the 125 new listings in 2014. The firm sees them together raising in the region of Rmb130bn (US$21bn), an increase of 65% from the Rmb78.6bn raised last year. This growth will be driven by improved capital market operations, as well as the possibility of a new IPO registration system. Despite such improvements domestically, the Chinese authorities may even encourage firms to list internationally as another means of boosting hard currency inflows, one that will be less volatile than encouraging foreign investment into locally-listed companies. Furthermore, the Stock Connect programme launched in mid-November 2014, while enabling international investment into Chinese stocks through expanding investment quotas, may in fact reduce Hong Kong’s importance as a listing destination for mainland Chinese firms. By connecting the Hong Kong and Shanghai exchanges the arrangement may encourage some firms to opt for a mainland listing, but others to look to the US if they want to access international funds. As such, the loosening of restrictions in China on repatriating foreign exchange raised and the success of the Alibaba IPO, together with persistent concerns about the domestic listing environment are likely to see the number of overseas listings – and the funds repatriated back to China – rise.